|

National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education

Standards of Professional Practice for Chief Diversity Officers*

(*The Standards of Professional Practice for Chief Diversity Officers are the exclusive property of NADOHE and may not be

copied or reproduced in any format without NADOHE’s prior written permission.)

Review and Revision of

NADOHE's Standards of Professional Practice for CDOs in Higher Education

(Fall 2018)

Standards Update Task Force Members:

(2018/2019)

Roger Worthington, Chair

Christine Stanley, Member

Daryl Smith, Member

NADOHE Presidential Task Force for the

Development of Standards of Professional Practice for CDOs

NOTE: Approved by the NADOHE Board of Directors October, 2014. The authors would like to thank the following individuals for their review and feedback of earlier drafts of this document: Molly Corbett Broad, Damon A. Williams, Glen Jones, Kenneth Bouyer, Ana Mari Cauce, Michael Stevenson, John Majer, Benjamin Reese, Paulette Granberry Russell, Archie W. Ervin, Elizabeth Ortiz, Debbie Seeberger, Jeanne Arnold, Shirley M. Collado, Kenneth Coopwood, Gilda G. Garcia, Joan Holmes, Kevin McDonald, Wanda Mitchell, Marilyn Sanders Mobley, Raji Rhys, Carmen Suarez, Gregory Vincent, William B. Harvey, and Arthur Dean. Correspondence regarding these standards may be sent to the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education ([email protected]).

2014 Task Force Members

Roger L. Worthington, University of Maryland

Christine A. Stanley, Texas A&M University

William T. Lewis, Sr., Virginia Tech University

Abstract

The National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education (NADOHE) have developed and approved Standards of Professional Practice for Chief Diversity Officers (CDOs). The standards established in this document are a formative advancement toward the increased professionalization of the CDO in institutions of higher education. These standards encompass a broad range of knowledge and practices that are reflected in the work of CDOs across differing professional and institutional contexts. The standards are useful as guideposts to help clarify and specify the scope and flexibility of the work of CDOs, and provide a set of guidelines to inform and assist individual administrators and institutions in aligning the work of CDOs on their campuses with the evolving characteristics of the profession. The standards take into account the relatively wide variations in professional backgrounds, expertise, organizational structures, fiscal resources, and scope of administrative authority that exist across institutional contexts. The standards of professional practice should not be applied rigidly or prescriptively to define who is “qualified” to do the work of diversity in higher education institutions or how diversity and inclusion offices should be configured. This document should be used as a tool to facilitate the advancement of significant and effective change on college and university campuses by emphasizing the role of the CDO as an organizational change agent for equity, diversity, and inclusion.

Keywords: chief diversity officer, diversity, higher education administration, National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education, standards of professional practice

National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education

Standards of Professional Practice for Chief Diversity Officers

A fundamental commitment to inclusive excellence embedded throughout higher education institutions is critical to the health and functioning of colleges and universities. Inclusive excellence starts at the highest level of administrative authority, is expressed prominently in institutional missions and strategic plans, and is supported through meaningful allocations of fiscal, human, and physical resources (AASCU/NASULGC Task Force on Diversity, 2005; Clayton-Pederson, O’Neill, & McTighe Musil, 2008; Leon, 2014; Williams, 2013; Williams, Berger, & McClendon, 2005; Williams & Wade-Golden, 2013). The emergence of the chief diversity officer (CDO) position as a senior administrative role in colleges and universities signals the critical need to expand representation across higher education among students, faculty, and administrators, as well as within the curriculum (Harvey, 2014). The strategies CDOs use for institutional transformation must be expansive, while at the same time taking into account the expertise of existing senior leaders, and advancing a diversity portfolio that reflects institutional values, mission, and culture (Stanley, 2014; Stevenson, 2014). Indeed, all higher education leaders should embody and demonstrate the critical values of equity, diversity, and inclusion, and should enable entire campus communities to access and articulate the contributions of and the rewards gained from an inclusive learning and working environment. Standards of professional practice help to facilitate a broader understanding of how the CDO functions, and are useful as guideposts to help clarify and specify the scope and flexibility of their work.

This document provides standards of professional practice for CDOs as members of the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education (NADOHE). These standards encompass a broad range of knowledge and practices that are reflected in the work of CDOs across contexts. This document should be used to guide current (and aspiring) CDOs in leading higher education institutions toward inclusive excellence and organizational change. The standards are both fluid and flexible to account for the wide variations in personal and professional backgrounds and characteristics of individual CDOs, as well as the broad range of institutional contexts within which they provide leadership. By no means should this document be interpreted as exhaustive, rigid, or overly prescriptive in nature. The flexibility of scope in the standards of professional practice is intended to honor the unique missions and strategic directions established by a broad array of higher education institutions. Thus, our professional standards do not aim to be fully comprehensive of every skill or competency exhibited by CDOs; however, equity, diversity and inclusion are invaluable threads to be woven throughout the fabric of institutional strategic plans.

The Work of the Presidential Task Force

Since its inception in 2007, the NADOHE Board of Directors has been engaged in dialogue and discussion about the professionalization of the chief diversity officer in higher education (Worthington, 2007). Over the course of time, the board developed a strategic plan that included an initiative to advance the professional standing of CDOs among higher education administrators (NADOHE, 2009). In 2012, NADOHE commissioned a presidential task force on the development of standards of professional practice for CDOs. The work of the task force began in earnest in 2013 via conference calls and electronic discussions to review and evaluate existing standards documents for other professions as well as the body of scholarly literature about CDOs.

A set of draft standards was developed and presented to the NADOHE board of directors and membership during the 2014 annual conference to obtain feedback and input during a three-hour professional development institute. The general sentiment during the institute was that the development of professional standards of practice was an historical step toward the professionalization of the field. However, there were some voices of concern that the standards should not be overly prescriptive or used as part of hiring or summative personnel decisions by presidents, provosts and trustees. There was broad consensus that the document should be inclusive of the range and scope of work and responsibilities of CDOs from a broad array of different types of institutions and practicing within a variety of different contexts.

The task force reviewed the feedback from the membership provided during the institute and further revised the document to integrate the scholarly literature, the task force charge, and the membership feedback. The revised document was shared with the board of directors and the NADOHE advisory board for further review. The final round of feedback was incorporated into the document, and it was prepared for publication. This is a “living document,” and we fully expect that there will be several new iterations across time that take into account the changing societal and higher education landscapes as well as the evolving nature and roles of the CDO in different contexts.

Overview and Literature Review

The CDO is a relatively new and rapidly growing executive leadership position in higher education administration (Williams, 2013; Williams & Wade-Golden, 2013). Standards of practice that are responsive to the dynamic landscape of higher education will help to advance the professionalization of the CDO role as it relates to serving the increasingly diverse demographics of our nation. It is essential that standards be fundamentally grounded in scholarship that establishes the foundation for the professional practices of CDOs. The brief literature review presented here offers a scaffolding of evidence that undergirds the breadth and depth of the work tackled by CDOs on behalf of all types of institutions.

Over the past two decades, there have been national trends toward (a) diversification of students and faculty in colleges and universities throughout higher education (Clayton-Petersen, Parker, Smith, Moreno, & Teraguchi, 2007; Turner, Gonzalez, & Wood, 2008), (b) assessment and improvement of the campus climate for diversity (Hart & Fellabaum, 2008; Hurtado, 1992; Hurtado, Griffin, Arellano, & Cuellar, 2008; Hurtado, Milem, Clayton-Peterson, &Allen, 1999; Worthington, 2008), (c) improvements in the representation and inclusion of diversity in the curriculum (Bensimon, 2004; Harvey, 2014; Milem, Chang, & Antonio, 2005; Smith, 2009), (d) development of intergroup dialogues in curricular and co-curricular student engagement (Gurin, Nagda, & Zuniga, 2013; Parker, Nemeroff, & Kelleher, 2011; Pasque, Chesler, Charbeneau, & Carlson, 2013; Smith, 2009; Toporek & Worthington, 2014; Worthington & Arévalo Avalos, in press); and (e) integration of broad campus-wide diversity plans integrated into institutional strategic planning (Clayton-Petersen, et al, 2007; Harvey, 2014; Milem, Chang, & Antonio, 2005; Smith, 2009; Stanley, 2014; Worthington, 2012). The breadth and scope of these advancements arise from foundational research that provides evidence for the educational and societal benefits of diversity in higher education (Alger, 2013; Antonio, Chang, Hakuta, Kenny, Levin, & Milem, 2004; Chang, 1999; Gurin, 1999; Gurin, Dey, Hurtado, & Gurin, 2002; Jakamura, 2008; Smith & Associates, 1997).

Generally, the CDO provides senior administrative leadership for strategic planning and implementation of mission-driven institutional diversity efforts (Williams & Wade-Golden, 2007). Institutions differ widely in terms of: (a) the level and scope of administrative authority given to the CDO (from “director” to “assistant/associate vice provost” to “vice president”); (b) the organizational structure of the offices headed by the CDO (from single-person offices to unit-based operations to broad-based, multifaceted divisional units); (c) the level of fiscal resources dedicated to the unit (e.g., operating budgets in the tens of thousands through tens of millions of dollars); (d) the level and types of qualifications required to perform the duties of the CDO (e.g., with degrees ranging from the Bachelor’s to the Ph.D. or J.D.), and (e) career tracks arising out of tenured academic faculty positions through nonacademic staff positions (e.g., student affairs, human resources or the business sector outside the university) (Williams & Wade-Golden, 2013; Witt/Keiffer, 2011). Very few CDOs have specialized educational credentials or foundational professional experiences that directly inform their roles and responsibilities. Over the course of time, individuals from a variety of professional backgrounds and educational credentials (e.g., law, psychology, higher education administration, business, engineering, humanities, medicine) have occupied the role of the CDO.

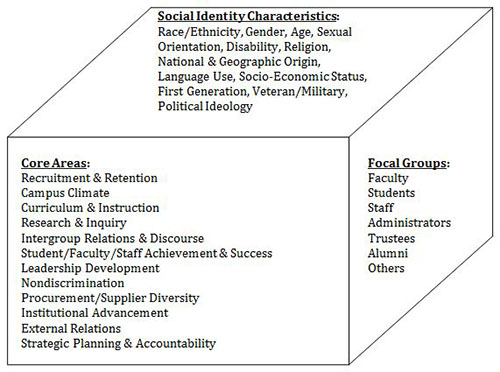

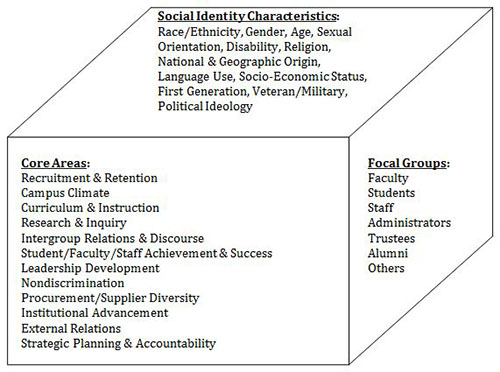

The CDO position was developed and has evolved over time to fill a senior leadership role that was not fully represented by earlier administrative posts with titles ranging from “minority affairs” to “multicultural specialists” to “equal opportunity officers” to “affirmative action officers,” among others (Williams & Wade-Golden, 2008). In addition, the contextual foundations of colleges and universities (e.g., institutional type, size, mission, values, and history) have substantial impact on the ways diversity leadership is conceptualized and configured within each institution (Leon, 2014). Furthermore, the work of the CDO is far-reaching and encompasses a wide range of social identities (e.g., race, gender, sexual orientation), focal groups (e.g., students, faculty and staff), and core areas applicable across focal groups and social identities (e.g., recruitment and retention, campus climate, curriculum and instruction) (Worthington, 2012; see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Three Dimensional Model of Higher Education Diversity Adapted from “Advancing Scholarship for the Diversity Imperative in Higher Education: An Editorial,” by R. L. Worthington, 2012, Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 5, p. 2. Copyright 2012 by the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education.

As the position of CDO within higher education administration continues to evolve, there is a need to establish a broad set of standards that align with accepted characteristics of professions. The professionalization of the CDO within higher education administration will advance in concordance with the development and acceptance of: (a) specialized expertise unique to the profession (e.g., education, knowledge, practices); (b) self-governance and accountability (e.g., a professional code of ethics; accreditation standards; educational certification); and (c) standards of practice (e.g., guidelines regarding the development and application of specialized expertise). Thus, although some models of professionalization (e.g., Wilensky, 1964 as cited in Williams and Wade-Golden, 2013) suggest that educational credentialing programs precede the development of standards of professional practice, the unique nature of the role of CDO in higher education warrants an alternate pathway. Given the wide variations in training, resources, reporting lines, and scope of responsibilities, as well as the complexities of diversity issues in higher education, it is critical for NADOHE to provide professional guidance to CDOs and higher education institutions in the form of standards of professional practice.

Standards of Professional Practice for CDOs

STANDARD ONE

Has the ability to envision and conceptualize the diversity mission of an institution through a broad and inclusive definition of diversity.

Institutions of higher education, like the U.S. population, are becoming increasingly diverse, not just in terms of racial and ethnic identity, but also age, cultural identity, religious and spiritual identity, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, physical and mental ability, nationality, social and economic status, and political and ideological perspectives. Chief diversity officers give voice to diversity in ways that continue to evolve in regional, national, and international contexts that extend beyond a traditional or historical understanding and application.

STANDARD TWO

Understands, and is able to articulate in verbal and written form, the importance of equity, inclusion, and diversity to the broader educational mission of higher education institutions.

The ability to effectively communicate the importance of equity, inclusion and diversity in verbal and written forms are fundamental practices necessary to advance the diversity mission of an institution through formal and informal interactions with stakeholders and constituents both inside and outside higher education institutions (e.g., faculty, staff, students, administrators, legislators, media, alumni, trustees, community members, and others). CDOs articulate the importance of equity, inclusion and diversity in a variety of ways (e.g., educational benefits, business case, social justice frameworks) that fit the broader educational missions of the institutions they serve.

STANDARD THREE

Understands the contexts, cultures, and politics within institutions that impact the implementation and management of effective diversity change efforts.

Colleges and universities are complex organizations that are accountable to internal, state, national, and global stakeholders. The internal contextual landscape is influenced by the interactions between and among these stakeholders, and affects the definition and implementation of the diversity mission. CDOs have the strategic vision to conceptualize their work to advance diversity, inclusion and equity, while simultaneously having the administrative acumen to be responsive to the broader contextual landscape.

STANDARD FOUR

Has knowledge and understanding of, and is able to articulate in verbal and written form, the range of evidence for the educational benefits that accrue to students through diversity, inclusion, and equity in higher education.

Existing research on the educational benefits of diversity to students provides a critical foundation for the work of chief diversity officers, and new findings continue to emerge in the scholarly literature. Basic fundamental knowledge and understanding of a wide range of evidence provides the basis for daily activities, diversity programming, leadership, and strategic planning at multiple levels of institutional operations.

STANDARD FIVE

Has an understanding of how curriculum development efforts may be used to advance the diversity mission of higher education institutions.

Curriculum is the purview of the faculty, and it also is a place where institutional diversity goals and learning outcomes are articulated, implemented, taught, and assessed. Chief diversity officers partner with faculty in curriculum development efforts to facilitate inclusive teaching and learning practices.

STANDARD SIX

Has an understanding of how institutional programming can be used to enhance the diversity mission of higher education institutions for faculty, students, staff, and administrators.

Colleges and universities vary with respect to mission, values, culture, and context. Chief diversity officers can identify and apply multiple sources of delivery methods to reach a diverse and complex audience within campus communities to enhance the diversity mission of an institution. These methods include, but are not limited to, presentations, workshops, seminars, focus group sessions, difficult dialogues, restorative justice, town hall meetings, conferences, institutes, and community outreach.

STANDARD SEVEN

Has an understanding of the procedural knowledge for responding to bias incidents when they occur on college or university campuses.

Bias incidents and hate crimes often occur on college and university campuses. Chief diversity officers serve as leaders regarding appropriate and effective responses to such incidents. In collaboration or partnership with others, chief diversity officers provide leadership in advancing appropriate and effective campus responses, such as (1) providing support and consultation to victims; (2) assisting in working through the institutional complaint process; (3) engaging law enforcement, regulatory agencies, or other campus authorities; and (4) providing consultation to campus leadership in communications with the media, as well as campus and community constituents, about the incidents. Where appropriate, CDOs facilitate, monitor and/or assist in record keeping and reporting activities that are required by law regarding such incidents (e.g., Clery Act; Title IX).

STANDARD EIGHT

Has basic knowledge of how various forms of institutional data can be used to benchmark and promote accountability for the diversity mission of higher education institutions.

Existing research provides compelling arguments for the use of various assessment tools to document the educational benefits of diversity and institutional effectiveness. Diversity efforts should be assessed beyond compositional data and satisfaction surveys. Basic knowledge of various methods of institutional data collection (e.g., academic achievement gaps, academic remediation, STEM participation, honors enrollments, graduation and persistence rates, recruitment and retention of students, faculty and staff) will help chief diversity officers promote accountability.

STANDARD NINE

Has an understanding of the application of campus climate research in the development and advancement of a positive and inclusive campus climate for diversity.

Campus climate research plays a central role in the development and advancement of strategic diversity planning. Although expertise as a researcher is not generally required, CDOs should be capable of providing oversight for periodic assessments related to campus climate for diversity, equity, and inclusion. Chief diversity officers can draw on the expertise of internal or external consultants to conceptualize and conduct research on their own campuses, and to utilize the findings to effect change and advance the development of institutional strategic planning efforts.

STANDARD TEN

Broadly understands the potential barriers that faculty face in the promotion and/or tenure process in the context of diversity-related professional activities (e.g., teaching, research, service).

Teaching, research, and service activities take many forms, and are the intellectual drivers and pillars for most colleges and universities. Working collaboratively with the academic community, chief diversity officers can support and advocate for faculty who work to challenge the hegemony of a disciplinary body of knowledge or who are historically underrepresented in the academy.

STANDARD ELEVEN

Has current and historical knowledge related to issues of nondiscrimination, access, and equity in higher education institutions.

Access and equity are central to the mission of higher education institutions, as are nondiscrimination laws, regulations, and policies, which have a longstanding history of advancement and modification. Institutional policies related to nondiscrimination may conform to, or be at variance with, federal and/or state mandates. For example, sexual orientation nondiscrimination may be incorporated into institutional policies despite lack of inclusion in federal or state laws. The chief diversity officer should have an awareness and understanding of the interplay among various laws, regulations, and policies regarding nondiscrimination.

STANDARD TWELVE

Has awareness and understanding of the various laws, regulations, and policies related to equity and diversity in higher education.

Institutions of higher education operate under the authority and jurisdiction of laws, regulations, and policies related to (or affecting) equity and diversity in higher education. In some cases, laws, regulations and policies mandate specific actions regarding issues of harassment, hate, nondiscrimination, equal access, equal treatment, and procurement/supplier diversity. In other instances, laws, regulations and policies place restrictions on the types and forms of activities chief diversity officers may pursue in advancing a diversity mission. Thus, awareness and understanding of the various national, state, and local laws, regulations, and policies are critical for the effective functioning of the CDO.

Summary and Conclusions

The standards set forth in this document are a formative advancement toward the increased professionalization of the chief diversity officer (CDO) in institutions of higher education. The role of the CDO was established on a fundamental passion for equity, diversity and inclusion, in addition to the important traits of administrative competence, professional collegiality, and personal character. These standards build upon core administrative skills and abilities, and do not replace them. First and foremost, CDOs must function within their own larger institutional contexts and administrative teams. CDOs cannot serve their institutions effectively in isolation, but instead must be part of a larger, cohesive team of leaders made up of presidents, provosts, trustees, and others sharing a common vision for the advancement of an institutional mission toward equity, diversity and inclusion.

Thus, these standards are presented as a set of guidelines to inform and assist individual administrators and institutions in aligning the work of the CDO on their campuses with the evolving characteristics of the profession, even as the work of CDOs continues to change across time and contexts. These standards of professional practice should not be applied prescriptively or rigidly. They should not be used to define who is “qualified” to do the work of diversity in higher education institutions, or how diversity and inclusion offices should be configured—some CDO roles are designed differently, which is the prerogative of the institution. As such, these standards are not intended to disrupt the variability of the work done by CDOs as defined by their respective institutions.

Fundamentally, CDOs are institutional change agents (Williams, 2013; Williams & Wade-Golden, 2013; Worthington, Hart, & Khairallah, 2009). Implemented in the right way, this document should be used as a tool to create important traction and relevance to spark the advancement of more significant and effective change on college and university campuses by prioritizing the role of the CDO in new spaces and conversations. These standards of professional practice are intended to advance a broader understanding of the complexities inherent to the work of diversity in higher education and the interplay between CDOs and other functional units throughout higher education institutions. These standards provide detail and clarity to the scope and flexibility of the work of CDOs, reflecting the wide range of expertise and practices fundamental to the work of CDOs that account for variations in the institutional contexts within which they serve.

References

Alger, J. R. (2013). A supreme challenge: Achieving the educational and societal benefits of diversity after the Supreme Court’s Fisher decision. . Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 6, 147-154.

American Association of State Colleges and Universities, & National Association of State Universities and Land-Grant Colleges Task Force on Diversity (2005). Now is the time: Meeting the challenge for a diverse academy. Washington, DC: Authors. Retrieved from: http://www.uiowa.edu/~success/documents/nitt_ebook.pdf

Antonio, A. L., Chang, M. J., Hakuta, K., Kenny, D. A., Levin, S., & Milem, J. (2004). Effects of racial diversity on complex thinking in college students. Psychological Science, 15, 507-510.

Bensimon, E. M. (2004). The diversity scorecard: A learning approach to institutional change. Change, 36, 45-52. Retrieved from http://cue.usc.edu/tools/Bensimon_The%20Diversity%20Scorecard.pdf

Chang, M. J. (1999). Does racial diversity matter?: The educational impact of a racially diverse undergraduate population. Journal of College Student Development, 40, 377-395.

Clayton-Pederson, A. R., O’Neill, N., & McTighe Musil, K. (2008). Making excellence inclusive: A framework for embedding diversity and inclusion into college and universities academic mission. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Clayton-Pederson, A. R., Parker, S., Smith, D. G., Moreno, J. F., & Teraguchi, D. H. (2007). Making a real difference with diversity: A guide to institutional change. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Gurin, P. (1999). The compelling need for diversity in higher education: Expert testimony in Gratz, et al. v. Bollinger, et al. Michigan Journal of Race & Law, 5, 363–425.

Gurin, P., Dey, E. L., Hurtado, S., & Gurin, G. (2002). Diversity and higher education: Theory and impact on educational outcomes. Harvard Educational Review, 72, 330-366.

Gurin, P., Nagda, B. R., Zuniga, X. (2013). Dialogue across difference: Practice, theory, and research on intergroup dialogues. New York: NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Hart, J., & Fellabaum, J. (2008). Analyzing campus climate studies: Seeking to define and understand. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 1, 222-234.

Harvey, W. B. (2014). Chief diversity officers and the wonderful world of academe. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 7, 92-100.

Hurtado, S. (1992). Campus racial climates: Contexts for conflict. Journal of Higher Education, 63, 539–569.

Hurtado, S., Griffin, K. A., Arellano, L., & Cuellar, M. (2008). Assessing the value of climate assessments: Progress and future directions. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 1, 204–221.

Hurtado, S., Milem, J., Clayton-Pederson, A., & Allen, W. (1999). Enacting diverse learning environments: Improving the climate for racial/ethnic diversity in higher education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Jayakumar, U. M. (2008). Can higher education meet the needs of an increasingly diverse society and global marketplace? Campus Diversity and Crosscultural Workforce Competencies Harvard Educational Review, 78, 615–651.

Leon, R. A. (2014). The chief diversity officer: An examination of CDO models and strategies. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 7, 77-91.

Milem, J. F., Chang, M. J., & Antonio, A. L. (2005). Making diversity work on campus: A research-based perspective. Washington, DC: Associationof American Colleges and Universities.

NADOHE (2009). Strategic Action Plan 2009-2014 Towards Inclusive Excellence. Author, Palm Beach Gardens, FL.

Parker, P., Nemeroff, T., & Kelleher, C. (2011). Training students to change their own campus culture through sustained diologue. In K. E. Maxwell, B. A. Nagda, & M. C. Thompson (Eds.) Facilitating intergroup dialogues: Bridging differences, catalyzing change. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Pasque, P. A., Chesler, M.A., Charbeneau, J., & Carlson, C. (2013). Pedagogical approaches to student racial conflict in the classroom. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 6. 1-16. doi: 10.1037/a0031695.

Smith, D. G. (2009). Diversity’s promise for higher education: Making it work. Baltimore, MD: John’s Hopkins University Press.

Smith, D. G., & Associates (1997). Diversity works: The emerging picture of how students benefit. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Stanley, C. A. (2014). The chief diversity officer: An examination of CDO models and strategies. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 7, 101-108.

Stevenson, M. R. (2014). Moving beyond the emergence of the CDO. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 7, 109-111.

Toporek, R. L., & Worthington, R. L. (2014). Integrating service learning and difficult dialogues pedagogy to advance social justice training. The Counseling Psychologist, online September 8, 2014. DOI: 10.1177/0011000014545090

Turner, C. S. V., Gonzalez, J. C., & Wood, J. L. (2008). Faculty of color in academe: What 20 years of literature tells us. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 1, 139–168.

Williams, D. A. (2013). Strategic Diversity Leadership. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishers.

Williams, D. A., Berger, J., & McClendon, S. (2005). Toward a model of inclusive excellence and change in higher education. Washington, DC: AAC&U.

Williams, D. A., & Wade-Golden, K. (2008). The chief diversity officer: A primer for college and university presidents. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

Williams, D. A. & Wade-Golden, K. (2013). The chief diversity officer: Strategy, structure, and change management. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishers.

Witt/Kieffer. (Summer, 2011). Chief diversity officers assume larger role. Retrieved from http://www.wittkieffer.com/file/thought-leadership/practice/CDO%20survey%20results%20August%202011.pdf

Worthington, R. L. (2007). The Professionalization of the Chief Diversity Officer. Presentation at the National Conference on Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education, San Francisco, CA (May 31, 2007).

Worthington, R. L. (2008). Measurement and assessment in campus climate research: A scientific imperative. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 1, 201-203.

Worthington, R. L. (2012). Advancing scholarship for the diversity imperative in higher education: An Editorial. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 5, 1-12.

Worthington, R. L., & Arévalo Avalos, M. R. (in press). Difficult dialogues in counselor training and higher education. In C. M. Alexander, J. M. Casas, L. A. Suzuki, & Jackson, M. (Eds.) Handbook of Multicultural Counseling, 4th, (pp. ##). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Worthington, R. L., Hart, J., Khairallah, T. (2009). Counselors as diversity change agents in higher education. In J. G. Ponterotto, J. M. Casas, L. A. Suzuki, C. M. Alexander (Eds.) Handbook of Multicultural Counseling, 3rd, (pp. 563-576). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

© National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education 2014

*The Standards of Professional Practice for Chief Diversity Officers are the exclusive property of NADOHE and may not be copied or reproduced in any format without NADOHE’s prior written permission.

|